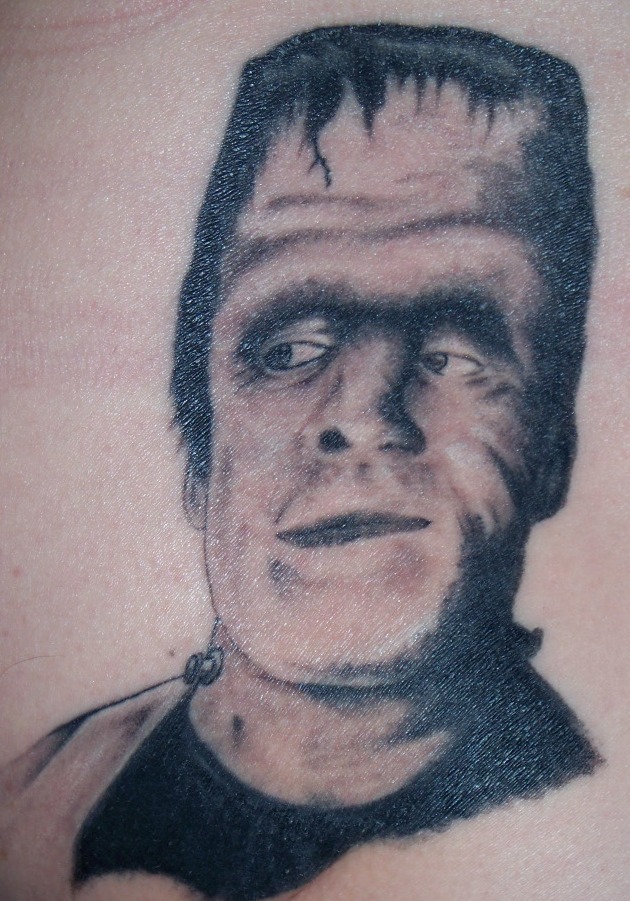

Another Great Tattoo!

Mark Martin, the owner of Georgia Boyz Ink Work in Dublin, didn’t always own his own business and have a family.

About 12 years ago, he was in prison, but he changed his life, and he’s helping others to do the same. Martin offers free tattoo removal for those who have gang and prison tattoos on their face and hands.

“The tattoo vanish is just another one of those things that if I can help somebody out because of the road that I traveled then I am willing to help them out,” said Martin.

He said talking to his grandpa in prison, made him realize that he had to change the direction his life was going in.

“My grandpa, he passed away. When I was incarcerated and locked up, I called him one day and he asked me to look out the window cause all my friends was standing there. And I went to look out the window and there wasn’t nobody standing there, so then I realized I had to change people, places and things to make my life better.”

Martin says many people along the way gave him a second chance and he hopes the tattoo removal does the same for other people who are just getting out of jail and looking to start over.

Martin is removing the facial tattoos of Christopher Truelove got out of jail in September and says the service is a great help.

“I mean people look at you, and they’re like you see a dude with horns on his face and you know, you’re like should I really give this guy a second chance,” said Truelove.

Truelove says he got those tattoos in prison and he’s glad to have Martin not only remove them but support him in turning his life around.

“It means alot it’s just a great push, it just makes you want to do right, you know what I mean. It’s just people behind you, it’s like yeah, you know it’s alright, you know it wakes you up in the morning for real,” said Truelove.

Martin also works with the Salvation Army. He’s collected over 400 pounds of food for the organization.

A tattoo is made by inserting indelible ink into the dermis layer of the skin to change the pigment. Tattoos on humans are a type of body modification, and tattoos on other animals are most commonly used for identification purposes. The first written reference to the word, “tattoo” (or Samoan “Tatau”) appears in the journal of Joseph Banks, the naturalist aboard Captain Cook‘s ship the HMS Endeavour in 1769: “I shall now mention the way they mark themselves indelibly, each of them is so marked by their humour or disposition”.

Tattooing has been practiced for centuries in many cultures spread throughout the world. The Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan, traditionally had facial tattoos. Today one can find Berbers of Tamazgha (North Africa), Māori of New Zealand, Hausa people of Northern Nigeria, Arabic people in East-Turkey and Atayal of Taiwan with facial tattoos. Tattooing was widespread among Polynesian peoples and among certain tribal groups in the Taiwan, Philippines, Borneo, Mentawai Islands, Africa, North America, South America, Mesoamerica, Europe, Japan, Cambodia, New Zealand and Micronesia. Indeed, the island of Great Britain takes its name from tattooing, with Britons translating as ‘people of the designs’ and the Picts, who originally inhabited the northern part of Britain, literally meaning ‘the painted people’.[1] British people remain the most tattooed in Europe.[1] Despite some taboos surrounding tattooing, the art continues to be popular in many parts of the world.

Since the 1990s, tattoos have become a mainstream part of global and Western fashion, common among both sexes, to all economic classes, and to age groups from the later teen years to middle age. By the 2010s, even the Barbie doll put out a tattooed Barbie in 2011, which was widely accepted, although it did attract some controversy.[2] In 2010 around 3 in 5 (62%) of Generation Y did not have any tattoos in the United States and three-fourths (75%) of Australians under 30 did not have any tattoos.[3]

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary gives the etymology of tattoo as “In 18th c. tattaow, tattow. From Polynesian tatau. In Tahitian, tatu.” The word tatau was introduced as a loan word into English, the pronunciation being changed to conform to English phonology as “tattoo”.[4] Sailors on later voyages both introduced the word and reintroduced the concept of tattooing to Europe.[5]

A tribal hand tattoo in Jaipur, India. Tattooing is a tradition among many indigenous people.

Tattoo enthusiasts may refer to tattoos as “Ink”, “Tats”, “Art”, “Pieces”, or “Work”; and to the tattooists as “Artists”. The latter usage is gaining greater support, with mainstream art galleries holding exhibitions of both conventional and custom tattoo designs. Beyond Skin, at the Museum of Croydon, is an example of this as it challenges the stereotypical view of tattoos and who has them. Copyrighted tattoo designs that are mass-produced and sent to tattoo artists are known as flash, a notable instance of industrial design. Flash sheets are prominently displayed in many tattoo parlors for the purpose of providing both inspiration and ready-made tattoo images to customers.

The Japanese word irezumi means “insertion of ink” and can mean tattoos using tebori, the traditional Japanese hand method, a Western-style machine, or for that matter, any method of tattooing using insertion of ink. The most common word used for traditional Japanese tattoo designs is Horimono. Japanese may use the word “tattoo” to mean non-Japanese styles of tattooing.

In Taiwan, facial tattoos of the Atayal tribe are named “Badasun”; they are used to demonstrate that an adult man can protect his homeland, and that an adult woman is qualified to weave cloth and perform housekeeping.[citation needed]

The anthropologist Ling Roth in 1900 described four methods of skin marking and suggested they be differentiated under the names of tatu, moko, cicatrix, and keloid.[6]

Tattooing has been a Eurasian practice at least since around Neolithic times. Ötzi the Iceman, dating from the fourth to fifth millennium BC, was found in the Ötz valley in the Alps and had approximately 57 carbon tattoos consisting of simple dots and lines on his lower spine, behind his left knee, and on his right ankle. These tattoos were thought to be a form of healing because of their placement which resembles acupuncture.[19] Other mummies bearing tattoos and dating from the end of the second millennium BC have been discovered, such as the Mummy of Amunet from ancient Egypt and the mummies at Pazyryk on the Ukok Plateau.[7]

Pre-Christian Germanic, Celtic and other central and northern European tribes were often heavily tattooed, according to surviving accounts. The Picts were famously tattooed (or scarified) with elaborate dark blue woad (or possibly copper for the blue tone) designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his Gallic Wars (54 BC).

Tattooing in Japan is thought to go back to the Paleolithic era, some ten thousand years ago.[citation needed] Various other cultures have had their own tattoo traditions, ranging from rubbing cuts and other wounds with ashes, to hand-pricking the skin to insert dyes.

Tattooing in the Western world today has its origins in Polynesia, and in the discovery of tatau by eighteenth century explorers. The Polynesian practice became popular among European sailors, before spreading to Western societies generally.[8]